The Infrastructure Cliff: How Dated Zoning Rules Push Property Taxes Higher

For many Minnesota homeowners, their 2026 property tax statements felt like a breaking point. Public hearings last December made it clear that rising taxes no longer feel sustainable for many households across the state. While the instinctive response is often to demand that cities tighten their belts or cut non-essential spending, in many communities, rising property taxes are not the result of runaway budgets. Instead, they are the result of long-deferred infrastructure costs colliding with rules that have long limited how many households help pay those costs.

Rising costs expose a deeper structural problem

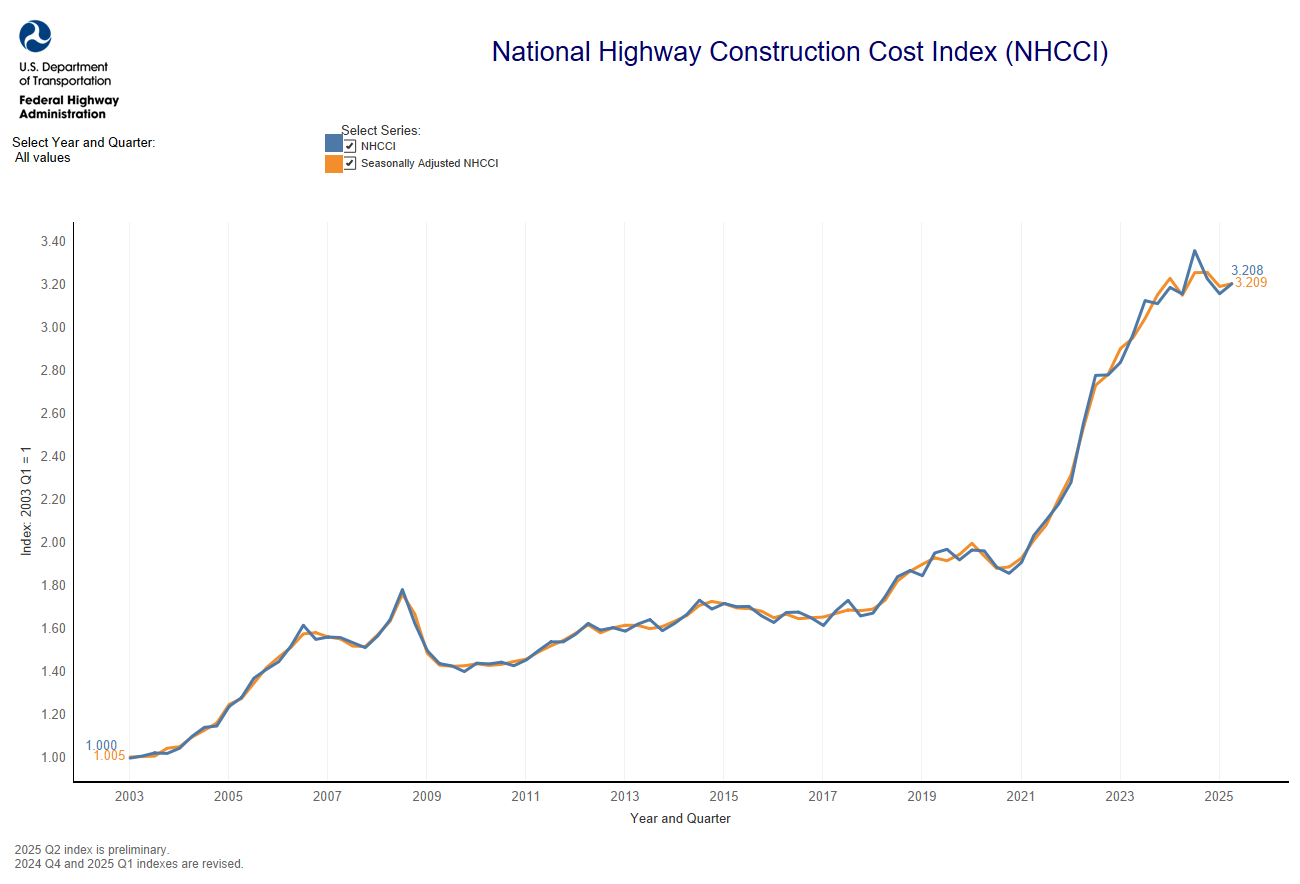

Just like the households they serve, local governments are facing rising costs for core public services. Repairing streets, maintaining utilities, and operating parks are significantly more expensive today than they were just a few decades ago. According to data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, the cost of road construction alone has more than tripled since the early 2000s.

But rising costs alone do not explain today’s property tax increases. Many of these pressures are rooted in development patterns inherited from the mid-20th century. In the decades following World War II, cities expanded rapidly. Infrastructure was new, maintenance needs were low, and steady growth added new households to the tax base year after year. For a long time, that pattern worked, keeping both housing and property taxes affordable.

What it actually did was delay the bill. Major infrastructure costs were deferred, not eliminated, and those deferred costs are now coming due.

When cities are built out, the math breaks down

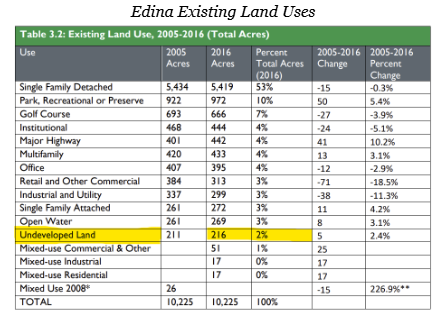

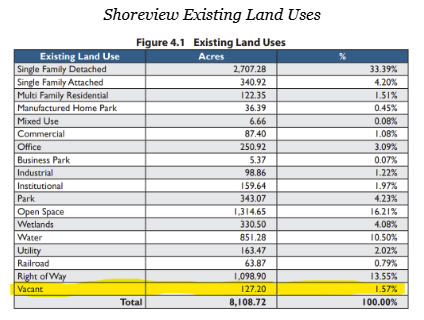

Today, many core cities and their suburban neighbors are largely built out, with little undeveloped land remaining that could accommodate new subdivisions without changes Today, many core cities and their suburban neighbors are largely built out, with little undeveloped land remaining that could accommodate new subdivisions without changes to current lot size requirements. According to their adopted 2040 comprehensive plans, only about 2 percent of land in Edina and roughly 1.6 percent of land in Shoreview is classified as vacant or undeveloped under their current zoning codes.

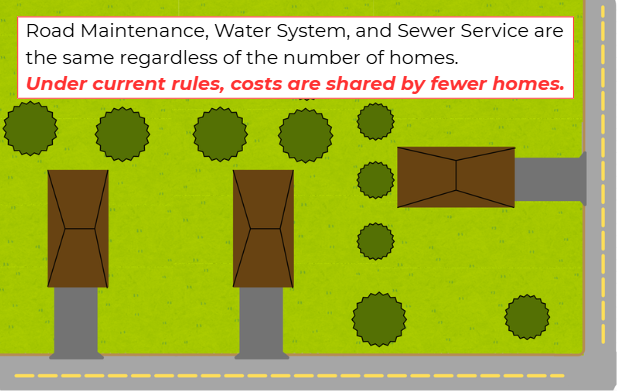

At the same time, streets, water lines, and sewer systems built in the 1950s through the 1970s are nearing the end of their useful lives and require full reconstruction rather than routine upkeep. These costs are unavoidable, even in communities that are growing slowly or not at all. Roads still need to be rebuilt so people can get to work and school. Pipes still need to be replaced to ensure clean drinking water and functioning sewer systems. Parks still need maintenance to remain usable community spaces.

Importantly, most suburban infrastructure was designed with the capacity to serve more households than exist today. In many cases, suburban residential streets were designed wider than necessary for their traffic volumes, often wider than streets in older cities like Minneapolis and St. Paul that support far more homes and daily activity.

What limits growth now is not traffic or utilities, but zoning rules that prevent neighborhoods from adapting. Suburban blocks built out in the 1960s often have the same number of households in 2026, even as maintenance costs have multiplied.

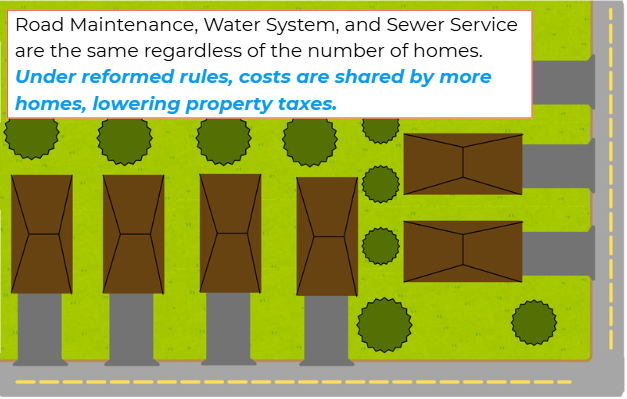

When the cost of maintaining streets and utilities rises, and the number of contributing households stays flat, property taxes go up. This is basic math, not a frivolous spending problem.

Why modest housing reform matters

Allowing modest increases in housing by permitting accessory dwelling units and smaller lot sizes, so that large properties can be subdivided, would bring more households into neighborhoods that already have streets, pipes, and public services. Because this infrastructure is already in place, these new homes rarely require major public investment. Instead, they spread the rising costs of infrastructure maintenance across more households.

In many cases, these new homes are added, not by tearing existing homes down, but by making use of underused space. Smaller housing types were once common, such as carriage houses before the 1940s, remain in demand, and fit comfortably within existing neighborhoods.

Housing policy is fiscal policy. Minnesotans feeling squeezed by the property tax increases of 2026 deserve land-use rules that allow their communities to adapt incrementally, rather than remain locked into development laws designed for a very different era. This year, the legislature has a chance to change this policy and pass the Yes to Homes bill. We urge them to do so.