The Hidden Rule Shaping Minnesota’s Housing Market

In the Land of 10,000 Lakes, Why 10,000 Square Feet?

Before a foundation is poured or a wall is framed, homes in Minnesota carry an invisible requirement: a minimum amount of land. Formally called a minimum lot size, this local zoning regulation sets the smallest parcel of land on which a home can legally be built.

Minimum lot sizes function as a regulatory floor. They determine how many homes can fit within a city’s boundaries and how much land must be attached to each one before construction even begins. If a zoning code requires 10,000 square feet, a property owner cannot divide land into 8,000-square-foot lots and build two homes, even if streets, utilities, and buyers are available.

In practice, that rule means every homebuyer must purchase a minimum amount of land, whether they want it or not. In many parts of the Twin Cities metro, land now represents nearly half or more of a home’s total value, according to research from the American Enterprise Institute. Requiring more land per home mandates higher prices.

The cost is not only financial. A 10,000-square-foot lot is nearly a quarter acre, roughly the size of a 30-car parking lot (or TWO full-size NBA courts). For a typical 2,000-square-foot home, well over half of that required lot space is yard that must be mowed, landscaped, watered, and maintained. The zoning code sets that minimum, not consumer preference.

Across the Twin Cities metro, minimum lot sizes in single-family zoning districts typically range between 9,000 and 11,000 square feet. In many communities, they are higher; in very few are they lower. That pattern raises a straightforward question: why these numbers? Why regulate minimum lot size?

Where Do These Laws Come From?

If minimum lot sizes influence how many homes can be built and how much land costs are embedded in each one, it is worth understanding how these standards came to be adopted in the first place.

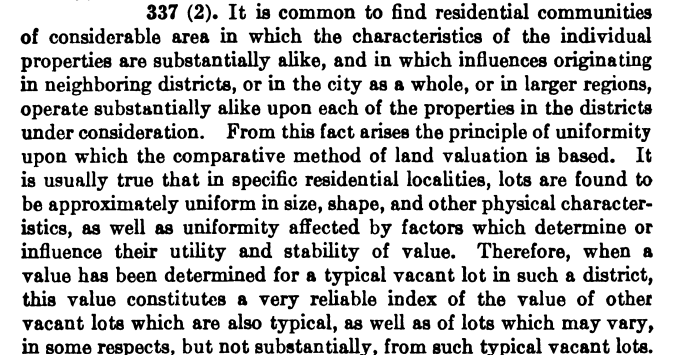

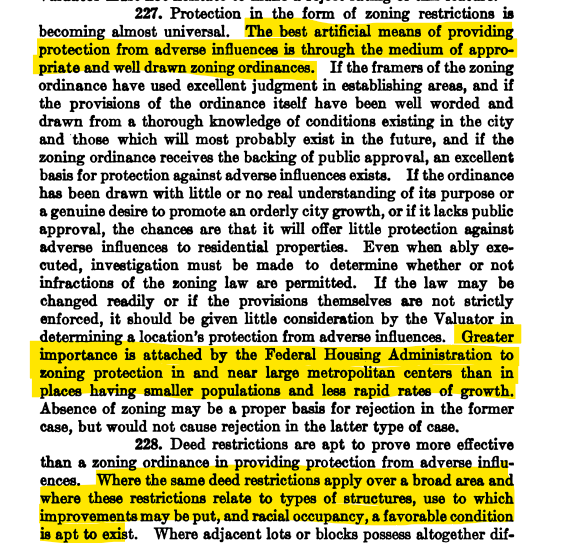

In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld local zoning authority in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., giving cities broad legal power to divide land into districts and regulate uses within them. A few years later, the Federal Housing Administration reshaped American development through mortgage insurance. To qualify for federally backed loans, subdivisions needed to meet underwriting standards that emphasized uniform residential development, particularly through predictable lot dimensions. Those same underwriting standards also reinforced racial segregation through practices now known as redlining and explicitly endorsed racially restrictive deed covenants.

Page 102 of FHA Manual.

Page 195 of the FHA - celebrates zoning, demands it in metro areas, immediately turns to celebrate racial covenants.

Between the late 1940s and early 1970s, suburban communities across the Twin Cities and the United States adopted comprehensive zoning codes. Minimum lot-size regulations were nearly ubiquitous in these early ordinances.

As farmland was subdivided into neighborhoods, roads, schools, and utilities had to be extended quickly to keep pace with rapid suburban growth. Zoning provided an orderly and legally vetted framework for managing that expansion, and minimum lot sizes served as a practical planning tool. Given the limited data and modeling capacity available, the standardization of lot size functioned as a simple proxy for density and growth management.

Minimum Lot Size Standards Today

What began as a practical growth-management tool for a specific moment in time has had staying power well beyond its origins. Over the last 75 years, zoning ordinances have grown dramatically in length and complexity. Communities that once operated under 30-page codes now administer documents running hundreds of pages, often with specialized staff to evaluate compliance.

This expansion is due to both improved technical capacity and evolving policy priorities. Cities today can model stormwater runoff, measure traffic impacts, and project infrastructure demand with far greater speed and precision than officials in the 1950s. They have also revised regulations to reflect changing views on land use, aesthetics, and neighborhood character.

Yet amid this growth in complexity and technical expertise, minimum lot sizes in single-family districts have remained essentially fixed.

Consider a few metro examples:

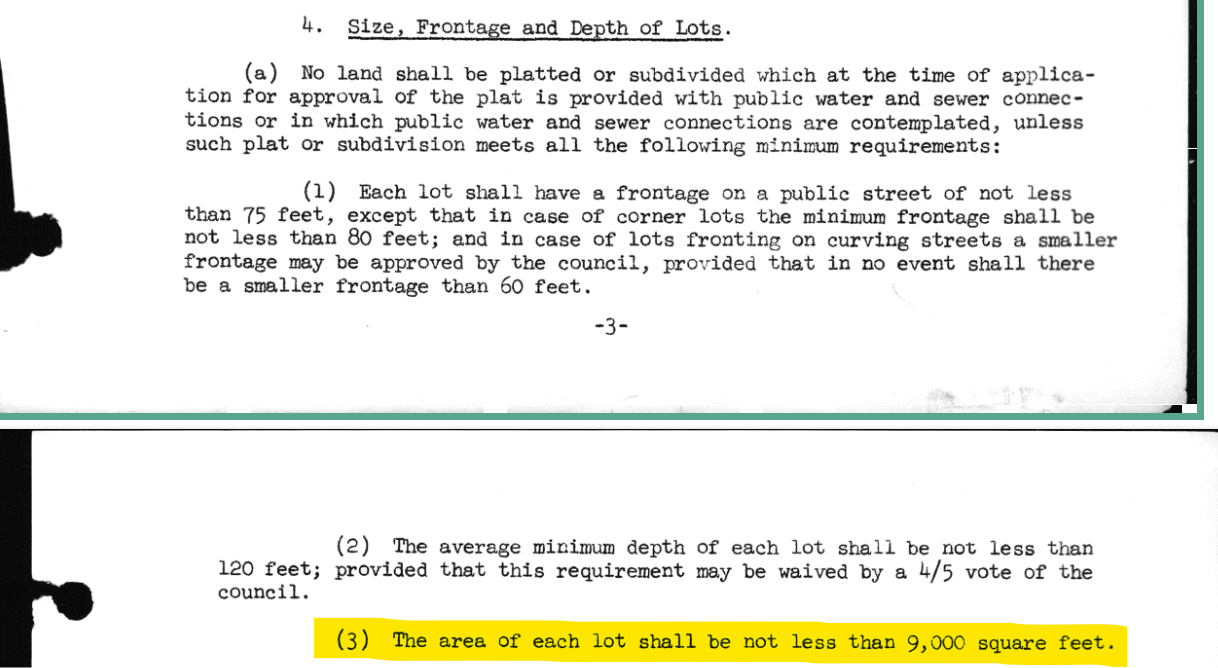

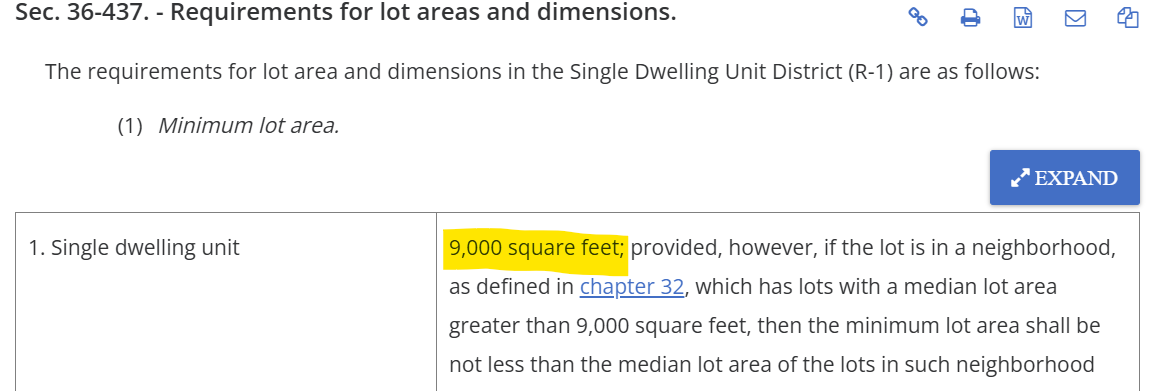

Edina established a 9,000-square-foot minimum lot size in 1953 as shown below (left). That standard remains 9,000 square feet today as shown below (right).

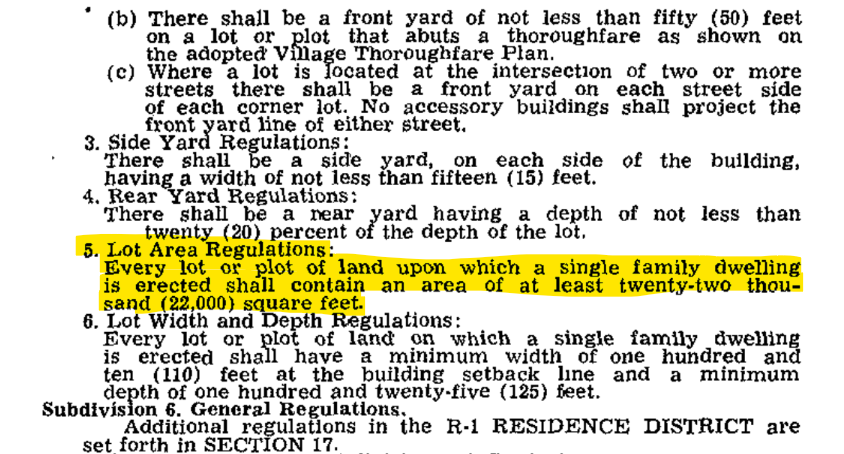

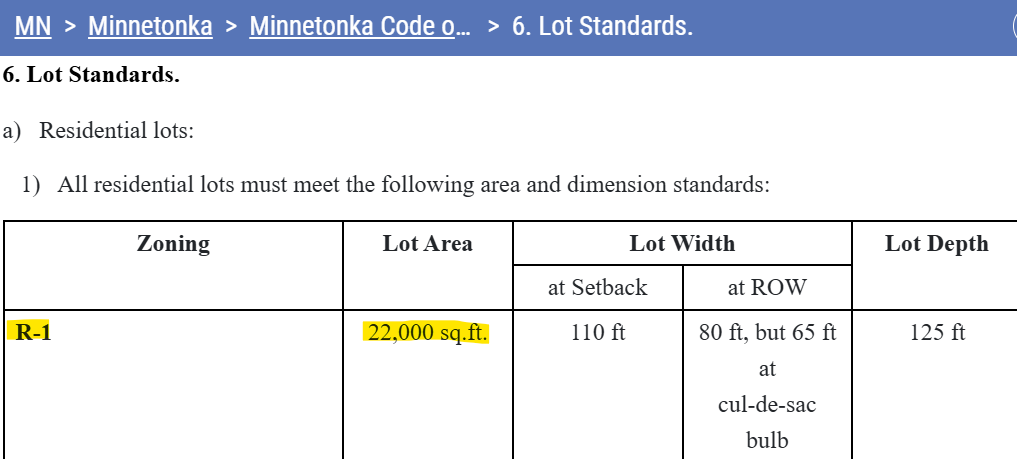

Minnetonka adopted a 22,000-square-foot minimum lot size for its primary single-family district in 1965 as shown below (left). Today, that standard remains 22,000 square feet as shown below (right), with smaller lots permitted only through special approvals.

Golden Valley’s 10,000-square-foot minimum and Apple Valley’s 11,000-square-foot standard both appear to date back to the 1980s, based on legislative references in their current codes. In both cases, publicly available records offer little documentation explaining when or why those specific numbers were originally established.

Tracing the precise origin of a minimum lot size is not always straightforward. In many cities, it requires digging through archived ordinances or submitting formal public records requests. Publicly viewable legislative histories are often fragmented, renumbered, or incomplete, as is the case with Golden Valley and Apple Valley. In Edina, the 1953 adoption of its 9,000-square-foot standard is buried on page 74 of a 434-page scanned document in the city’s online repository titled “Ordinances 1952–1980’s File 2.”

Why Haven’t These Standards Changed?

The difficulty in tracing the origin of minimum lot sizes is not just a niche curiosity; it also helps explain the durability of these standards.

Elected officials and planning commissioners inherit zoning codes they did not write, just as state and federal lawmakers inherit statutes enacted decades earlier. In the absence of a clear legislative record explaining why a specific number was chosen, it is easy to assume it serves an important purpose and leave it in place.

Minimum lot-size standards are also simple. Unlike stormwater modeling or traffic analysis, a square-footage requirement does not require specialized expertise or ongoing measurement. It functions as a blunt and easily administered proxy for density and housing form. Because it is visible and straightforward, it can feel like an essential safeguard, even as more precise infrastructure, design, and environmental standards now exist elsewhere in the code.

Ultimately, there is no single explanation for why these standards persist. Institutional inertia, administrative simplicity, and political caution all likely play a role. What is clear is that many of today’s minimum lot sizes were established under very different technical and economic conditions than those cities face now.

That reality has surfaced in recent legislative debates. As the state legislature has considered proposals requiring cities to substantially reduce minimum lot-size standards, the disagreement has centered less on whether the existing numbers remain technically justified and more on who has the authority to set them. In fact, one of the organizations opposing reform acknowledges in its own housing policy materials that lowering minimum lot sizes can improve housing affordability.

The Need for State Reform

The path forward to move beyond highly restrictive minimum lot-size standards is state legislation. Addressing these rules one city at a time would be slow and fragmented. Minneapolis and Saint Paul account for just 23 percent of the seven-county metro population. The remaining 77 percent live in more than 175 separate jurisdictions, each with its own zoning code and lot-size requirements. Reforming these laws locally would require more than 175 separate legislative debates and actions. That kind of coordinated change has largely failed to occur over the past 50 years.

The Yes to Homes Act would expand housing supply and improve affordability by lowering minimum lot-size floors that fix the amount of land required per home at levels established decades ago. Amid today’s housing shortage, the amount of land required per home is not a minor detail. It is a central driver of cost.

For Minnesota to meaningfully address housing affordability, lawmakers should lower minimum lot-size floors and support reforms like the Yes to Homes-supported bills.